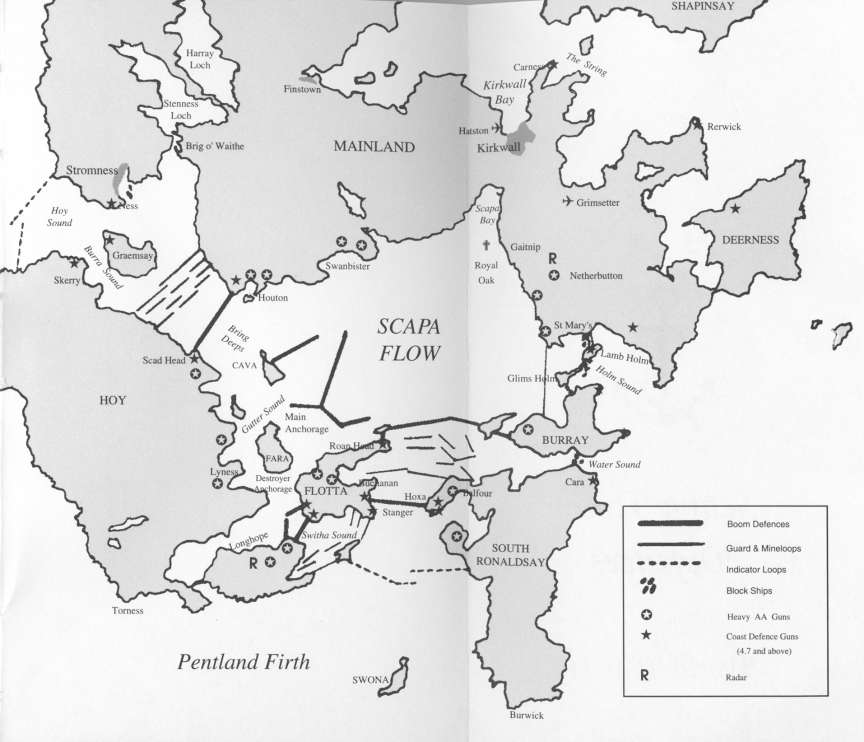

It was August 1914 before the Admiralty at last approved the defences for Scapa Flow. St Margaret’s Hope became a subsidiary base, which employed as many as two thousand men to do the work. The first submarine obstructions were little more than buoys moored across the Channels with herring nets strung between them. In November more robust steel nets and block ships were sunk across the eastern channels. These old merchant ships were brought up to the Flow without any ballast, and so were extremely light. It was very difficult to sink them in the right positions as the tides could run up to nine knots through Holm Sound. Eventually they were all successfully sunk correctly, and soon became part of the scenery until the more effective Churchill Barriers, with roads running across the top were built in the Second World War.

The block ships were particularly conspicuous in Holm Sound, especially the elegant shape of the former Royal Mail Steam Packet Company steamer Thames. She had once been commanded by Admiral Jellicoe’s father, and was a graceful three masted two funnel steamer, with a clipper bowsprit. When she was sunk, by the simple expedient of blowing her bottom out, she settled up right, and still gave the impression that she was still sailing on into Lamb Holm. Lying either side of her, to complete the blockage of the channel, were three other ships. The Numidian was a former Alland Line Trans Atlantic passenger ship, the Arangi came from the New Zealand line, and completely submerged was the Minieh.

After the First war the local fishermen kicked up about the inconvenience of not being able to use the Eastern Channels, and after a bit of argy bargy, the Admiralty said it would do something but then procrastinated and stonewalled for years, saying it was all too difficult. This was rightly seen as complete humbug buy the locals, as only a few miles away from these block ships, one of the greatest salvage operations in history was being carried out with salvaged German Battleships and Cruisers popping up all over the place. Eventually in 1929 the Admiralty gave the go ahead to remove the Thames and some other block ships, and so clear the navigable channel of Kirk Sound. They then handed over ownership of all the block ships to the County Council, and they in turn handed over the removal operation of the Thames to James Mitchell and Son of Dundee, on a no cure no pay basis. Bad move.

The Company was very confident, and work began in the summer of 1930 plugging all the holes in the hull. Unfortunately by the time the winter weather stopped proceedings, the Thames still wasn’t ready to lift. Work resumed in May 1931, but in July the Company announced that it would be abandoning the work. After nearly two years of toil it was considered impossible to re float the Thames, as her hull was ‘as thin as sixpence’. So there she stayed, gently rotting away, when suddenly she was back in the spotlight as one dark night in Gunter Prien in U47 committed one of the most daring raids of the U-boat war by creeping into Scapa Flow and torpedoing the Royal Oak with catastrophic results.

It turned out that the channel he came in by, which was supposed to be impassable to submarines, was in fact perfectly navigable, and that the Admiralty knew about it as long ago as 26 may 1939, nearly four months before War broke out. Once more the Admiralty wanted to save money, so they ignored the report sent in by the survey vessel H.M.S.Scott, which noted that the supposed blocked channel was in fact 400 ft wide, with a depth of over two fathoms at low tide. The ‘experts’ at the Admiralty considered a determined attack on the Flow as ‘unlikely’. After sinking the Royal Oak, Prien successfully negotiated the channel on the south side of Kirk Sound, passing close to the uninhabited island of Lamb Holm, almost scraping the barnacles of the Thames as he slid past to safety. In his log, Prien recorded the Thames’ two masts and funnels as a ‘schooner’.

At the end of the War steel was in short supply, so the thousands of tons lying in the shallows looked to be a useful resource. One by one all the block ships, including the Thames were stripped of any useful metal and steel plate, and their remains left to rust where they lay, and most are still there today.

I dived this wreck in 1985, and this is what I wrote in my notes.

Viz 15 ft at a depth of 50 ft. very silty. so a careless fin stirs it all up The Thames wreckage is jumbled up with what is left of the others, and seems to be lying on its side. Along one side is a whole row of portholes and as I drifted in through a hole in the hull, there almost covered by the mud was a loose porthole. Lots of other twisted plate and bits and pieces, but a porthole will do nicely.The rest of the wreckage is almost impossible to orientate on as its just a jumble of metal tossed by the scrappers into the shallows. if you dont stir it up though its very entertaining.