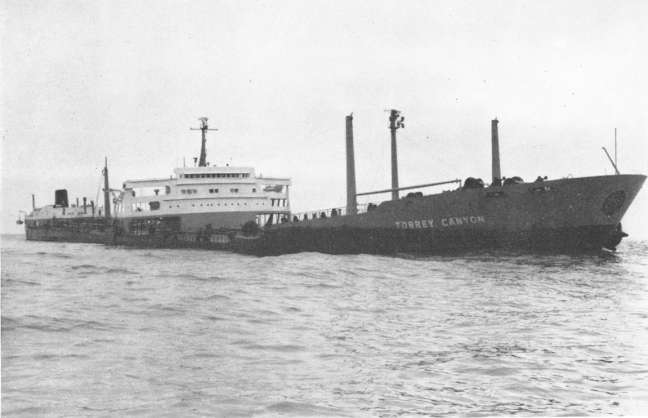

Anyone looking at a chart of the Scilly 1sles soon realizes that this small Island group is just one huge trap. Over the centuries well over two thousand ships have been wrecked around it’s trecherous shore, giving the Islands one of the greatest concentrations of shipwrecks anywhere in the world. The variety is quite staggering, ranging from H.M.S. Association, that celebrated flagship of Sir Cloudesly Shovel, to that infamous supertanker the Torrey Canyon, with just about every type of ship in between.

From the divers point of view, the Scillies have those two compulsive indients, clear water and enough dive sites to beat all but the worst weather. Recently I spent a week vith Sub Aqua Scilly ( don’t think that’s running now ) diving on ten different vrecks, and all though all have their own facination, three sites really stood out, each in it’s own way demonstrating vhy the Scillies is such a wreck divers paradise.

The first site gives really good value because it contains two wrecks, the Plympton and the Hathor, one stuck right on top of the other. The Plympton, a steamship of 2869 tons was on it’s way from Falmouth to Dublin with a cargo of maize. On the night of 14 April 1909 she encountered thick fog, and with her foghorn sounding off at full blast she steamed full til t onto the Lethergus reef vhere she stuck fast. Her crew of twenty three were all landed safely and then the locals got down to the serious business of stripping the wreck. Unfortunately whilst work was still in progress, the high tidefloated the Plympton off the reef. whereupon she immediately turned over and sank, killing two men who were still inside the hull.

Eleven years later the 7060 ton German steamship Hathor was being towed to Portland after breaking down near the Azores. As she reached the Scillies a fierce gale erupted which parted the havsers of her two tugs. The gale was considered to severe to risk reconecting the tow, and so on 2 December 1920 the Hathor was abandoned to the storm and eventualy hit the Lethergus Rocks sinking right across the remains of the Plympton. The Plympton now lies in 120 feet of water on a very rocky bottom. She is well broken up, but her bows, although upside down are still more or less intact. The Hathor’s wreckage clothed in a profusion of large plumuose anemones is further up the reef in about 80 feet, and lies right across that of the Plympton.

Underwater the wrecks present a tremendous sight. Both are surrounded by huge boulders and high rocy pinacles, and over the years they have become completely locked together. A huge iron propeller still connected to it’s shaft lies alongside a stern section still complete with it’s railings and a derrick. Spars and mangled iron plate lie scattered all around together with other large sections of wreckage. Further down in the gloom can just be seen the bottom of the Plympton’s bow. So jumbled have the wrecks become that it is often difficult to see where one starts and the other ends. With so much to see, a dozen dives would really be necessary to sort everything out which maybe explaines why these wrecks are so popular.

The next wreck is out on the Golden Ball Bar and is of the 7176 ton Panamanian steamship the Mando. She was outward bound from Hampton Roads for Rotterdam, loaded with coal. On 21 January 1955 she lost her way in thick fog, ran aground on the Golden Ball Bar and quickly became a total loss. Now most of the Mando lies 50 feet down on a fairly flat rocy shelf, with her stern section further down in nearly 100 feet. All though well broken up the Mando still has a lot to offer in the way of large pieces of wreckage. The propeller shafts are particularly worth inspection as you can just about squeeze inside them. The most interesting part of the wreck however, is the remains of the engine room which overhangs deep gullies, making inspection of all it’s nooks and crannies very easy. All around lie large brass elbows from broken steam pipes, thick connecting rods, and all manner of other bits and pieces. The amount of brass on this wreck is really amazing. Parts of the wreck still contain all sorts of block ‘half’ bearings still locked around their shafts. Some are nearly three feet long, and all are made of solid brass. If you are a metal merchant or just an honest grubber, this wreck really should not be missed.

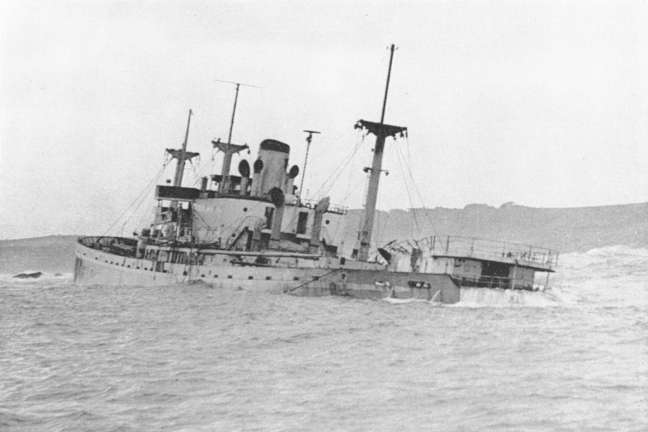

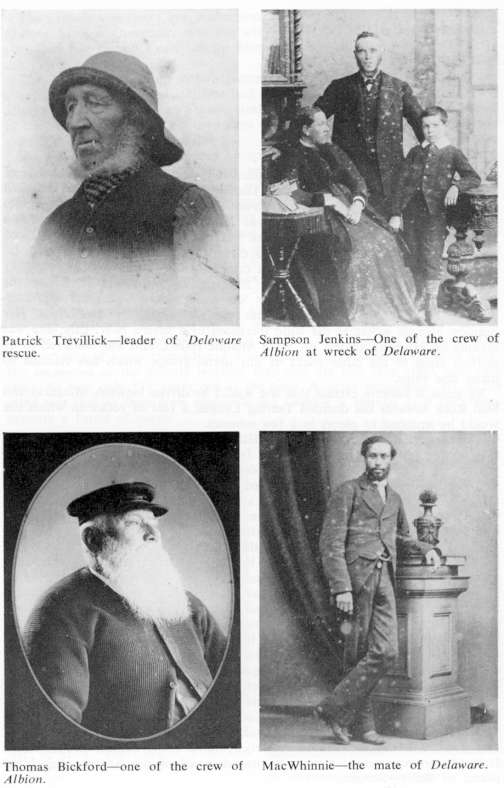

The last wreck is that of the 3423 ton steamship Delaware, outward bound from Liverpool to Calcutta carrying a cargo of silk. The Delaware was smashed to pieces on the ledges between the islands of Bryer and Samson during an exceptionally savage storm on 20 December 1871. The rescue of her five survivors involyed carrying a lifeboat across one of the islands, and assumed such epic proportions, that eyen today it is considered to be one of the bravest rescues ever carried out. Even so it was not without a touch of humour. Two of the survivors, convinced that the islanders were savages, barricaded themselves on a beach and pelted their would be rescuers with rocks, untill persuaded that they stood more chance of drowning than of being eaten by the Scillonians.

Today those ledges are named after the Delaware, and the remains of her wreckage now lie in 65 feet of water, well broken up except for the remains of the engine room which stands about 25 feet high. It seems to be on three levels, and since most of the sides are missing it is quite easy to swim around the large cog wheels and rods that almost fill the interior. At the very bottom, stuck away in a dark corner are three large brass elbows which despite considerable efforts still remain firmly concreted to the rocky bottom. The Delaware is not spectacular, nor is there a terrific amount of wreckage, so it is difficult to say quite why it is different. Maybe it’s just that , everyone seems to say off it, “what a good dive” and after all there cannot be a much better recomendation than that.

In the past the Scillies have relied on wrecking to help support their community, and today the wrecks are still contributing to the island economy as a major tourist attractiot A visitor cannot escape from the sense of history that permeates the islands, and it is this experience of living history,coupled with the amazing variety of wrecks, which makes the Scilly Islands unique.

Vic says

For anyone who is interested, here is a full account of the heroic rescue of the survivors from the SS Delaware.

Ferdinando Liguoro says

Dear Sirs,

Thanks a lot for showing me photo and news about SS Mando. My brother Giovanni was onboard as Radio Officer in that right moment. Now he died on 2001. Now I will print the picture and will have it with me carefully. I was Radio Office as well. But fortunately I didn’t live that adventure.

Thank you sirs so much. It is a piece of history.

John says

Interesting…I dived on the plymton in 1985 as a newly trained naval diver…it was my first ever free dive just swimming down with a group…fantastic sight I remember the huge boilers..I’d forgotten the top vessels name..

Richard says

Anyone know where the ships bell for the Hathor is, it was recovered from the wreck in 1975 and sold, I wondered if it was calling time in a pub somewhere, I think it was sold by ‘trader Grey’ of Penzance.