In 1940 Britain was fighting alone against an all conquering German war machine. Europe was completely crushed, and in the Atlantic more than one hundred and fifty ships, totalling more than a million tons had been destroyed. It soon became obvious that the U boats were sinking ships faster than we could build them. In desperation a British Merchant Ship Building Mission went to the USA to try and order the ships which were so urgently needed if the battle of the Atlantic was to be won.

Although America was still neutral, they were well aware of the problems facing us, and after some initial wrangling with the ship builders it was decided to prefabricate ships to a British design as this would speed up their building and ultimate delivery. Unfortunately the ships were not very pretty to look at, and there were many critics including President Roosevelt who called them ‘dreadful looking objects’. However you cannot go about giving ships a bad name, and soon somebody hit on the idea of calling the ships a Liberty Fleet.

The idea rapidly caught on and soon the ships themselves were being called Liberty Ships. They could not have picked a better name because Liberty Ships is exactly what they turned out to be. In their hundreds these ships ferried men and materials all over the world. Without them the war could have been lost simply because the Allied supply lines would have been stretched beyond breaking point through lack of sufficient ships. In 1945 the tide had started to turn for the Allies, but still the Liberty ships kept transporting those vital war supplies.

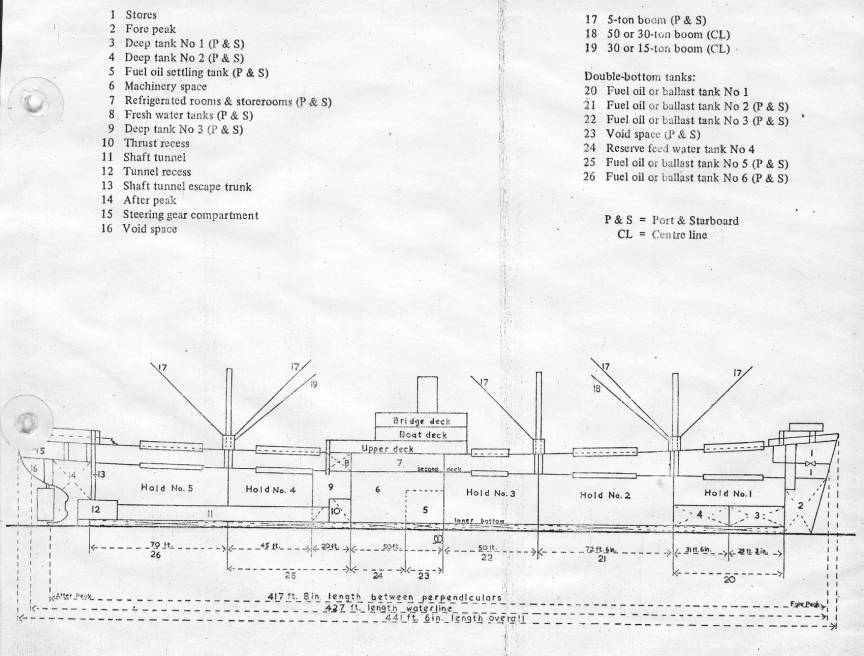

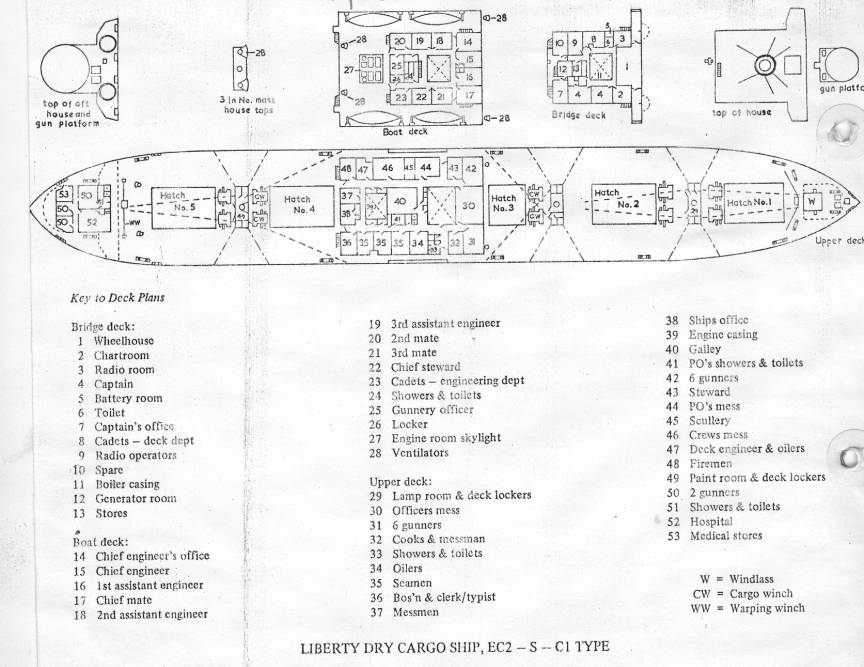

One of the ships involved in these trans shipments was the James Egan Layne. Built in By the Delta Shipbuilding Company of New Orleans she was 400 feet long and weighed just over 7000 tons, and during March 1945 she was engaged on a voyage from Barry in Wales to Ghent, loaded with United States Army engineering stores. By the afternoon of 21 March the Layne was about seven miles from the Plymouth Breakwater, just on the edge of one of the most profitable of all the U boat hunting grounds. She must have been spotted very quickly, because at 2.35 that same afternoon U-boat 1195 hit the Layne with a torpedo, which sliced a great hole in her side.

Her holds quickly flooded as did her engine room, but the Layne was not going to sink without a fight. For nearly eight hours the crew kept the vessel afloat, but the Captain realising that she was finished set course as best he could for the shore hoping to beach her. He very nearly made it. By now the Layne was taking in water faster than the crew could get rid of it. So at half past ten that night the ship gently went aground in seventy feet of water, snugly held firm on the sandy bottom of Whitsands Bay. Thankfully there were no casualties, and eventually most of the cargo was salvaged. In the end the loss to the war effort was minimal, but the gain to the future generations of sports divers was to prove considerable.

In the early sixties diving in England was just starting to take off. Even so it was an expensive business, and not many wrecks had been discovered that were suitable for the amateur diver. It is hardly surprising then that the James Egan Layne, situated in relatively shallow and clear water should become so popular. Here was a wreck within easy reach of the shore by small boat. Her masts and part of her superstructure still showed above water, making her exact location childsplay. The wreck was on an even keel and virtually intact. You could swim through the holds and down into the engine spaces. The gash where the torpedo struck was plain to see, and the whole wreck looked like something from a Hollywood film set. No one who dived on the Layne could forget it, and over the years it became the most famous and dived on wreck in all England.

Today the James Egan Layne still lies upright on her sandy bed, but her superstructure and masts have long been swept away by the winter storms to lie scattered around her on the sandy bottom. The wreck after some thirty-five years is starting to break up, but still it is possible to see what she was once like. The bows are still intact and their flair is still well defined, as are the sides of her hull which loom out of the sand like black cliffs. Ironically the storm damage over the last few years has actually made the inside of the wreck more accessible. The holds are jammed with twisted iron plates, pipes, old ladders and all the other paraphernalia of a wrecked ship. Even so there is little danger of getting lost, as you can easily see an exit hole either from the hold that you are entering, or in the side of the ship itself.

If you want souvenirs, one of the holds contains hundreds of pickaxe heads all neatly lined up in rows. If that doesn’t appeal you can take your pick of various locomotive wheels or pulley wheels. Near the stern the ship is virtually cut in half where the torpedo hit it, and again there is a mountain of metal debris with one of the masts hanging out from the ships deck and supported by the rest of the wreckage. Once more there are lots of holes and caverns to explore, but here some care should be taken as quite frequently pieces of metal fall from above into the holds and could cause a nasty accident. This whole area is littered with bollards, winches, coils of wire hawser, and many other deck fittings, and over all this preside the fish.

All wrecks have an abundance of marine life, but the Layne seems to have more than its fair share. The holds are often full of silver bass, whilst the bows are patrolled by watchful shoals of pollack. Pouting make up most of the bottom cover, weaving over all the debris like a brown zebra crossing, and lurking almost underneath the keel are some very large ling. Wrasse in all shapes and colours, large green and pink plumrose anemones, small starfish with colourful coats, the list is endless. On a summers day this wreck is better than a tropical reef and almost as colourful. Visibility is often forty to fifty feet, and one of my most enduring memories is of vaulting over the guardrails on the main deck, and slowly descending sixty feet down the side of the ship watching my exaust bubbles rising to the surface, after being trapped by the light coating of dead mans fingers that now cover the rusting plates. It was a magical experience, but only one of many that can be had on this fantastic wreck.

Since the Sixties many other wrecks have been discovered all over the British Isles. But not withstanding their popularity, the Layne has become almost a national dive site, and very many divers have a special regard for her. So much so that recently when Trinity House thought to disperse the wreck with explosives, there was such a howl of protest that they were forced to reconsider. Time however will soon do the job for Trinity House. So if you want to dive on a piece of history do it now, because soon only the legend will remain.

Paul says

Stern section

The stern section though not dived as regularly as the main wreckage is well worth a visit. The stern is situated about 25mtrs from the main wreckage.The easiest way to find it is to swim out at in a south westerly direction off the port side were the main wreckage has collapsed into the seabed (most dives start at the bows so this will intail swimming the length of the wreck until the hull ends). Once the stern is located you will be met with a profusion of deadmans fingers and plumose anemones ,the stern of the JEL seems to have more than its fair share of these,almost to the point that as you approach it takes on a ghostly appearance as its silouete comes into view. On the seabed there are various pieces of associated wreckage,where the stern meets the seabed there is a small hole,probably about two foot square,looking inside you will see a pile of shells complete with brass fuse cones. The stern on the Egan layne was fitted with a gun, evidence of this can still be seen in the form of a ring of about 4ft diameter at which point the gun mounting would have been situated.

Paul.