The “Base Fuse, Impact” as shown below, was fitted into the base of a shell’s projectile. This served a two fold purpose,

1) to ensure a level of “Bore Safety” and prevent the shell exploding prior to being fired, and,

2) to ensure that, once fired, the shell would explode upon hitting something. This was arranged by having a firing pin in the base fuse set into a piece of soft metal in such a way that it was impossible for it to set off the main charge.

Once the round had been fired inertia would force the soft metal to the rear of the pin and expose the sharp tip. Now if an object was struck the pin would fly forward and the point would set off the shells explosive charge.

“Base fuses” were frequently replaced by solid plugs when the shell was fired for training purposes, the shell was then filled with an inert substance that would replicate the “Live” rounds weight and so unaffect its ballistic characteristics. There many other types of “Base impact fuses” and were mainly fitted into the larger types of shellThey could also be fitted with a delay feature that would ensure that the shell would explode once it had passed through an object and its fragments, as well as the explosion itself, would damage material and men behind whatever it had penetrated.

As armour plate became more effective a new type of shell evolved and this was the “Palliser chilled tip armour piercing shell”. As its name suggests it had a tip that was formed in a special mold that would ensure it was rapidly cooled when being cast. This resulted in an extremely hard metal that could penetrate any armour plate then existing. It wasn’t until WW11, and the introduction of much superior armour plate, that these shot were defeated. A shell utilizing a shaped charge warhead that depended upon the “Monroe effect” had to be developed to defeat these newer armours, and even now in 2002 the contest between “Armour” and “Shell” continues unabated. Modern armours consist mainly of “Composites”, meaning layers of differing materials, and even “Reactive” materials that will explode on being hit and thus dissipate the energy of the impacting shot or shell.

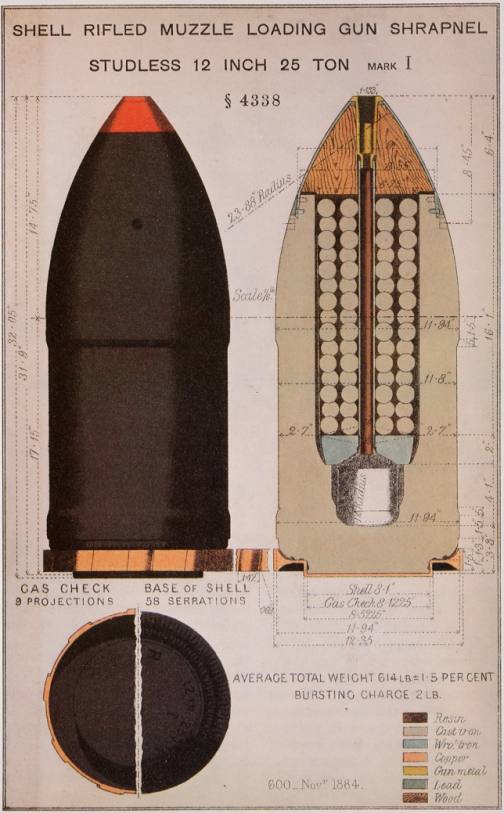

Nose mounted fuses were also developed in many guises and these enabled a shell to be exploded in the air, after a set amount of time had elapsed, before it had hit anything. This found its greatest use in WW1 when it was used to explode “Shrapnell Shells” above and in front of an advancing enemy. It did this to such effect that many, many more men were killed by artillery fired “Shrapnell shells” than from any other cause.

Extract from Bombs and Bullets DVD

Below is a drawing showing the type of shell to which the above fuse would have been fitted. After firing, the time set on the fuse would expire, and the fuse would fire down the shells central tube to ignite the powder charge contained in its base behind the charge of balls. This powder would then explode and force the balls forward along the shells line of flight like some huge shotgun blast. Its killing power over a large area was tremendous, and it replaced the much earlier “Case” and “Canister” shells as the prime “Man-killing” weapon on the battlefield.

There are many other applications for delayed action fuses, chief amongst them being in an Anti- Aircraft role, and because of WW11, there are many thousands of fuses from successfully exploded shells, and also complete un-exploded rounds where the fuse failed, laying on the sea bed waiting to be found.. Once the round had been fired, the time delay set on the fuse should have ensured that the shell exploded at the end of its flight, however, this didn’t always happen and so an impact element was built into the fuse to ensure it exploded on hitting the ground or the sea, again this didn’t always occur, so there are many shells on the sea bed that have not exploded correctly. This was ok if the gun was firing out over the sea, but caused problems if being fired over land, as the population then not only had to contend with falling bombs but also with faulty AAA shells. Where small weapons were involved such as the 2pdr. Pom Pom or the 40mm. Bofors this wasn’t too much of a problem, but if you had some 3.7″ or even larger 6″ shells coming down then it could ruin your whole day quite abruptly.

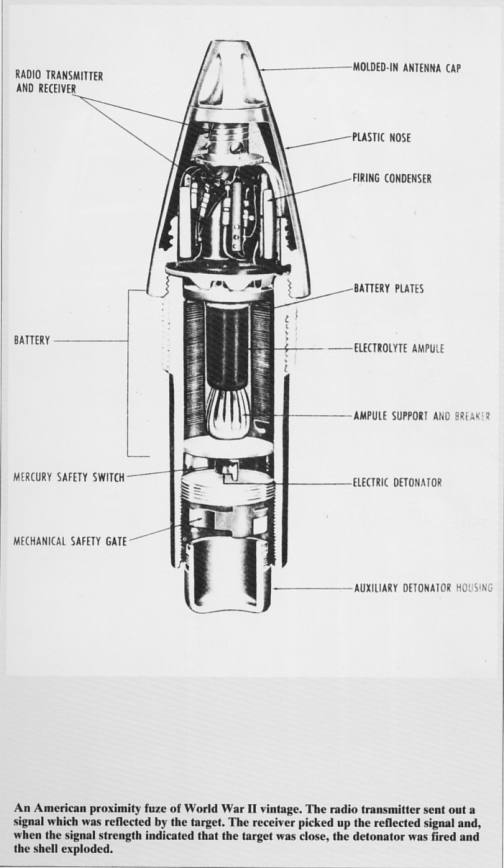

As technology improved it became possible to fit a form of Radar into a shell fuse and this could be set so as to detonate the shell when the reflected return from the target ensured that it was close enough to be destroyed by the exploding shell. These “Proximity shells” were a saviour for the South East of England during WW11 when the Germans started sending over large no.s. of V1’s.. The fuses ensured that the AAA batteries were able to shoot the majority down before they reached any major population centres.

The fuse depended upon the shock of firing breaking a capsule of electrolyte, and the spin of the shells rotation rapidly spread this over the cells of a battery. After a short time the battery was powered up and would energize a small built in Radar emitter.

This would then transmit its signal through the Radar transparent plastic nose cone of the fuse, and , when it received a strong enough return signal, it would detonate the shell . These fuses can also be found on the sea bed from the rounds fired by HMS Cambridge during AAA training for the Navy. Because of the materials used in their construction they rapidly rot away and are seldom worth recovering.

Clady Page says

I have a heavy metal fuse box canister with many letters and numbers all around it. It is roughly a 14 inch (guessing because it not with me) cube with a heavy latch on all four sides of the top and two handles. I can read nose fuze mk.8 and 1942. Some of the writing that I can make out or guess at are c.p.pri.mk.19 — 2.s.ord.co. 1942…spdn8g18 3 gr ns …lead foll…in.vel.2700 r.s….n.h.g.o qndg.officer….ag or 86 – ctgs. spdnig4g. — Any information appreciated